This multi-part post is as a result of reading the critique of Darwin's Origin of Species, "Un-Science, Not Science, Adverse To Faith" (1878)

This multi-part post is as a result of reading the critique of Darwin's Origin of Species, "Un-Science, Not Science, Adverse To Faith" (1878)

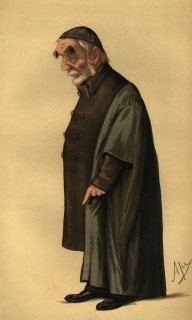

[Left: Edward Bouverie Pusey, Project Canterbury]

by Darwin's contemporary, Edward B. Pusey (1800-1882), the Oxford Professor of Hebrew (and the author of a great commentary on Daniel which I own), and then Darwin's response to it in a private letter to a C. Ridley (who apparently was H.N. Ridley, director of the Botanical Garden of Singapore) who had written to Darwin asking him questions about it.

In his letter Darwin gives two further examples of his dishonesty when it came to protecting his theory, claiming that: 1) "Dr. Pusey was mistaken in imagining that I wrote the 'Origin ' with any relation whatever to Theology" and 2) "when I was collecting facts for the 'Origin,' my belief in what is called a personal God was as firm as that of Dr. Pusey himself" (my emphasis):

"I just skimmed through Dr. Pusey's sermon, as published in the Guardian, but it did [not] seem to me worthy of any attention. As I have never answered criticisms excepting those made by scientific men, I am not willing that this letter should be published; but I have no objection to your saying that you sent me the three questions, and that I answered that Dr. Pusey was mistaken in imagining that I wrote the 'Origin ' with any relation whatever to Theology. I should have thought that this would have been evident to any one who had taken the trouble to read the book, more especially as in the opening lines of the introduction I specify how the subject arose in my mind. This answer disposes of your two other questions; but I may add that many years ago, when I was collecting facts for the 'Origin,' my belief in what is called a personal God was as firm as that of Dr. Pusey himself, and as to the eternity of matter I have never troubled myself about such insoluble questions. Dr. Pusey's attack will be as powerless to retard by a day the belief in Evolution, as were the virulent attacks made by divines fifty years ago against Geology, and the still older ones of the Catholic Church against Galileo, for the public is wise enough always to follow Scientific men when they agree on any subject ; and now there is almost complete unanimity amongst Biologists about Evolution, though there is still considerable difference as to the means, such as how far natural selection has acted, and how far external conditions, or whether there exists some mysterious innate tendency to perfectability. " (Darwin, C.R., Letter to C. Ridley, November 28, 1878, in Darwin, F., ed., "The Life and Letters of Charles Darwin," [1898], Basic Books: New York NY, Vol. II., 1959, reprint, pp.411-412).

As to 1) Darwin's claim that "Dr. Pusey was mistaken in imagining that I wrote the 'Origin ' with any relation whatever to Theology" (my emphasis), this is false and Darwin must have known it to be false.

That is, it is yet another example of what eminent British geneticist C.D. Darlington (1903-1981) noted, that "Darwin was slippery" employing "a flexible strategy which is not to be reconciled with even average intellectual integrity (my emphasis)":

"These were virtues or accidents. But side by side with them were what I shall describe as vices. These, we now have to admit, were almost as great a help, almost as valuable a combination in achieving his success, as the virtues that accompanied them. By that I mean his public and political success in mass conversion. These vices were of three kinds: a conservative outlook in every respect except the evolutionary hypothesis; a failure to recognize or to relate his own ideas, his larger ideas, with those of others working in the same field; and a flexible strategy which is not to be reconciled with even average intellectual integrity: by contrast with Wallace, Lyell, Hooker, Chambers or even Spencer, Darwin was slippery." (Darlington, C.D., "Darwin's Place in History," Basil Blackwell: Oxford UK, 1959, p.60)

First, as I have documented, in my web page: "Darwin's references to `creation' (or its cognates) in his The Origin of Species, 6th Edition, 1872," Darwin used the word "creation" (or its cognates) in his final edition of his Origin of Species at least 109 times, and almost always in a pejorative sense.

Here, for example, are eleven instances of where Darwin in his Origin attacked what he claimed was the then "ordinary view" of creation (my emphasis):

"It would be difficult to give any rational explanation of the affinities of the blind cave-animals to the other inhabitants of the two continents on the ordinary view of their independent creation." (Darwin, C.R., "The Origin of Species By Means of Natural Selection," John Murray: London, Sixth Edition, 1872, Reprinted, 1882, p.111)

"On the ordinary view of each species having been independently created, why should that part of the structure, which differs from the same part in other independently created species of the same genus, be more variable than those parts which are closely alike in the several species? I do not see that any explanation can be given. But on the view that species are only strongly marked and fixed varieties, we might expect often to find them still continuing to vary in those parts of their structure which have varied within a moderately recent period, and which have thus come to differ." (Ibid., pp.122-123)

"In the vegetable kingdom we have a case of analogous variation, in the enlarged stems, or as commonly called roots, of the Swedish turnip and Ruta baga, plants which several botanists rank as varieties produced by cultivation from a common parent: if this be not so, the case will then be one of analogous variation in two so-called distinct species; and to these a third may be added, namely, the common turnip. According to the ordinary view of each species having been independently created, we should have to attribute this similarity in the enlarged stems of these three plants, not to the vera causa of community of descent, and a consequent tendency to vary in a like manner, but to three separated yet closely related acts of creation. " (Ibid., p.125)

"Mammals offer another and similar case. I have carefully searched the oldest voyages, and have not found a single instance, free from doubt, of a terrestrial mammal (excluding domesticated animals kept by the natives) inhabiting an island situated above 300 miles from a continent or great continental island; and many islands situated at a much less distance are equally barren. ... Yet it cannot be said that small islands will not support at least small mammals, for they occur in many parts of the world on very small islands, when lying close to a continent; and hardly an island can be named on which our smaller quadrupeds have not become naturalised and greatly multiplied. It cannot be said, on the ordinary view of creation, that there has not been time for the creation of mammals; many volcanic islands are sufficiently ancient, as shown by the stupendous degradation which they have suffered, and by their tertiary strata: there has also been time for the production of endemic species belonging to other classes; and on continents it is known that new species of mammals appear and disappear at a quicker rate than other and lower animals. Although terrestrial mammals do not occur on oceanic islands, aerial mammals do occur on almost every island. ... Why, it may be asked, has the supposed creative force produced bats and no other mammals on remote islands? On my view this question can easily be answered; for no terrestrial mammal can be transported across a wide space of sea, but bats can fly across." (Ibid., pp.350-351)

"The naturalist, looking at the inhabitants of these volcanic islands in the Pacific, distant several hundred miles from the continent, feels that he is standing on American land. Why should this be so? why should the species which are supposed to have been created in the Galapagos archipelago, and nowhere else, bear so plainly the stamp of affinity to those created in America? There is nothing in the conditions of life, in the geological nature of the islands, in their height of climate, or in the proportions in which the several classes are associated together, which closely resembles the conditions of the South American cost: in fact, there is a considerable dissimilarity in all these respects. On the other hand, there is a considerable degree of resemblance in the volcanic nature of the soil, in the climate, height and size of the islands, between the Galapagos and Cape Verde archipelagoes: but what an entire and absolute difference in their inhabitants! The inhabitants of the Cape Verde Islands are related to those of Africa, like those of the Galapagos to America. Facts such as these, admit of no sort of explanation on the ordinary view of independent creation: whereas on the view here maintained, it is obvious that the Galapagos Islands would be likely to receive colonists from America ? and the Cape Verde Islands from Africa; such colonists would be liable to modification, - the principle of the inheritance still betraying their original birthplace." (Ibid., p.354)

"The relations just discussed, - namely, lower organisms ranging more widely than the higher, - some of the species of widely-ranging genera themselves ranging widely, - such facts, as alpine, lacustrine, and marsh productions being generally related to those which live on the surrounding low lands and dry lands, - the striking relationship between the inhabitants of islands and those of the nearest mainland - the still closer relationship of the distinct inhabitants of the islands in the same archipelago - are inexplicable on the ordinary view of the independent creation of each species, but are explicable if we admit colonisation from the nearest or readiest source, together with the subsequent adaptation of the colonists to their new homes." (Ibid., p.359)

"We can see why characters derived from the embryo should be of equal importance with those derived from the adult, for a natural classification of course includes all ages. But it is by no means obvious, on the ordinary view, why the structure of the embryo should be more important for this purpose than that of the adult, which alone plays its full part in the economy of nature. Yet it has been strongly urged by those great naturalists, Milne Edwards and Agassiz, that embryological characters are the most important of all; and this doctrine has very generally been admitted as true." (Ibid., p.368)

"Geoffroy St. Hilaire has strongly insisted on the high importance of relative position or connexion in homologous parts; they may differ to almost any extent in form and size, and yet remain connected together in the same invariable order. We never find, for instance, the bones of the arm and fore-arm, or of the thigh and leg, transposed. Hence the same names can be given to the homologous bones in widely different animals. ... Nothing can be more hopeless than to attempt to explain this similarity of pattern in members of the same class, by utility or by the doctrine of final causes. The hopelessness of the attempt has been expressly admitted by Owen in his most interesting work on the 'Nature of Limbs.' On the ordinary view of the independent creation of each being, we can only say that so it is; - that it has pleased the Creator to construct all the animals and plants in each great class on a uniform plan; but this is not a scientific explanation. " (Ibid., pp.382-383)

"There is another and equally curious branch of our subject; namely, serial homologies, or the comparison of the different parts or organs in the same individual, and not of the same parts or organs in different members of the same class. Most physiologists believe that the bones of the skull are homologous - that is, correspond in number and in relative connexion - with the elemental parts of a certain number of vertebræ. The anterior and posterior limbs in all the higher vertebrate classes are plainly homologous. So it is with the wonderfully complex jaws and legs of crustaceans. It is familiar to almost every one, that in a flower the relative position of the sepals, petals, stamens, and pistils, as well as their intimate structure, are intelligible on the view that they consist of metamorphosed leaves arranged in a spire. In monstrous plants, we often get direct evidence of the possibility of one organ being transformed into another; and we can actually see, during the early or embryonic stages of development in flowers, as well as in crustaceans and many other animals, that organs, which when mature become extremely different are at first exactly alike. How inexplicable are the cases of serial homologies on the ordinary view of creation!" (Ibid., p.384)

"As natural selection acts by competition, it adapts and improves the inhabitants of each country only in relation to their co-inhabitants; so that we need feel no surprise at the species of any one country, although on the ordinary view supposed to have been created and specially adapted for that country, being beaten and supplanted by the naturalised productions from another land. Nor ought we to marvel if all the contrivances in nature be not, as far as we can judge, absolutely perfect, as in the case even of the human eye; or if some of them be abhorrent to our ideas of fitness. We need not marvel at the sting of the bee, when used against an enemy, causing the bee's own death; at drones being produced in such great numbers for one single act, and being then slaughtered by their sterile sisters; at the astonishing waste of pollen by our fir-trees; at the instinctive hatred of the queen-bee for her own fertile daughters; at ichneumonidæ feeding within the living bodies of caterpillars; or at other such cases. The wonder indeed is, on the theory of natural selection, that more cases of the want of absolute perfection have not been detected." (Ibid., pp.414-415)

"On the ordinary view of each species having been independently created, why should specific characters, or those by which the species of the same genus differ from each other, be more variable than generic characters in which they all agree? Why, for instance, should the colour of a flower be more likely to vary in any one species of a genus, if the other species possess differently coloured flowers, than if all possessed the same coloured flowers? (Ibid., pp.415-416).

Continued in part #2.

Stephen E. Jones, BSc. (Biology).

Exodus 9:13-35. 13Then the LORD said to Moses, "Get up early in the morning, confront Pharaoh and say to him, 'This is what the LORD, the God of the Hebrews, says: Let my people go, so that they may worship me, 14or this time I will send the full force of my plagues against you and against your officials and your people, so you may know that there is no one like me in all the earth. 15For by now I could have stretched out my hand and struck you and your people with a plague that would have wiped you off the earth. 16But I have raised you up for this very purpose, that I might show you my power and that my name might be proclaimed in all the earth. 17You still set yourself against my people and will not let them go. 18Therefore, at this time tomorrow I will send the worst hailstorm that has ever fallen on Egypt, from the day it was founded till now. 19Give an order now to bring your livestock and everything you have in the field to a place of shelter, because the hail will fall on every man and animal that has not been brought in and is still out in the field, and they will die.' " 20Those officials of Pharaoh who feared the word of the LORD hurried to bring their slaves and their livestock inside. 21But those who ignored the word of the LORD left their slaves and livestock in the field. 22Then the LORD said to Moses, "Stretch out your hand toward the sky so that hail will fall all over Egypt-on men and animals and on everything growing in the fields of Egypt." 23When Moses stretched out his staff toward the sky, the LORD sent thunder and hail, and lightning flashed down to the ground. So the LORD rained hail on the land of Egypt; 24hail fell and lightning flashed back and forth. It was the worst storm in all the land of Egypt since it had become a nation. 25Throughout Egypt hail struck everything in the fields-both men and animals; it beat down everything growing in the fields and stripped every tree. 26The only place it did not hail was the land of Goshen, where the Israelites were. 27Then Pharaoh summoned Moses and Aaron. "This time I have sinned," he said to them. "The LORD is in the right, and I and my people are in the wrong. 28Pray to the LORD, for we have had enough thunder and hail. I will let you go; you don't have to stay any longer." 29Moses replied, "When I have gone out of the city, I will spread out my hands in prayer to the LORD. The thunder will stop and there will be no more hail, so you may know that the earth is the LORD's. 30But I know that you and your officials still do not fear the LORD God." 31(The flax and barley were destroyed, since the barley had headed and the flax was in bloom. 32The wheat and spelt, however, were not destroyed, because they ripen later.) 33Then Moses left Pharaoh and went out of the city. He spread out his hands toward the LORD; the thunder and hail stopped, and the rain no longer poured down on the land. 34When Pharaoh saw that the rain and hail and thunder had stopped, he sinned again: He and his officials hardened their hearts. 35So Pharaoh's heart was hard and he would not let the Israelites go, just as the LORD had said through Moses.

No comments:

Post a Comment